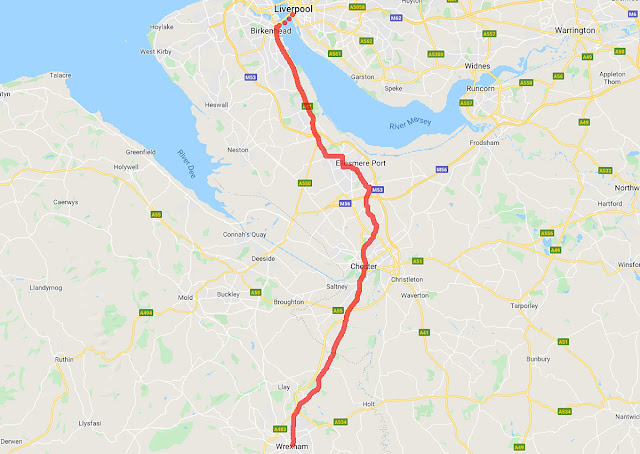

Day 15 - Mersey Mission

Wrexham to Liverpool

It’s a fairly short day today so I permit myself the luxury of a leisurely English Breakfast. It's therefore quite late as I begin my walk back into Wrexham town centre. The town's fleshpots are mostly closed up apart from a few dispirited cleaners busily scraping sick and empty pizza boxes from their doorways and Wrexham seems to wear a friendlier face today.

|

| Wrexham bus station |

I make straight for the town’s bus station and my first bus of the day, an Arriva service to Chester, which soon has us romping out of town and speeding back towards England. Quite suddenly the road tips over a steep escarpment and drops quickly onto a vast, low plain with fields and tall stands of poplars stretching almost as far as the eye can see. It's a bit of a shock; having travelled to Wrexham from the Welsh hills I had no sense of the town being anything other than relatively low lying. It's surprisingly to find that it is apparently at a far higher altitude than the surrounding countryside.

We cross back into England somewhere between the villages of Rosset on the Welsh side and Pulford on the English. The flatness of the plain encourages our driver to put his foot down so Chester quickly looms into view.

The City of Chester is stunning, in a conventionally attractive ‘gee, honey, look at that’ sort of way. It’s real picture postcard stuff but it's also immediately obvious why people would want to come and shop here. The city boasts street after medieval street of attractive, superbly-preserved Elizabethan timber-framed buildings skilfully converted into retail units with the names of every major High Street brand and designer above the door. This is retail therapy writ large.

|

| Chester |

One of the city's unique retail attractions is The Rows, pedestrian walkways at first floor level which are accessed by means of a set of stone steps from the pavement. You can wander for miles along these covered walkways looking at attractive shop windows on one side and out across the street the other. Its elegant, quaint and beautifully preserved and a great way to view the city.

Chester’s perfunctory bus station, by contrast, which once again is carefully hidden from view, has the appearance of having been built from a design scratched out on the back of a fag packet, though maybe it just looks dismal in contrast to the architectural fireworks everywhere else in Chester’s city centre. No... no, it is dismal. Fortunately, I don't have to linger as my bus to Birkenhead is waiting for me.

I have been deeply impressed – astonished even – by the sheer scale of the English countryside. The ride into London from Land’s End, and my trip up from Watford to Wrexham, has been through vast tracts of the greenest, most beautiful countryside it’s possible to imagine, and I genuinely had no idea it was here. Yes, I could see all the green bits on my pocket atlas but I don't think I fully appreciated what that meant. To see it close up, and to keep on seeing it as it morphs seamlessly from one county into another, is a complete revelation. I honestly hadn’t realised just how beautiful Britain is.

|

| Chester bus station. 'Nuff said. |

Now, though, I’m leaving the countryside and entering that region carelessly referred to as ‘The North'. It's only a handful of miles from the hills and meadows but the factories and housing estates I am now travelling through make it seem like a different continent. Our bus is no longer a thrice-daily incursion into a village’s slumber, or four times if its Market Day, but just a tiny fraction of the constant ebb and flow of the ceaseless traffic. How different it all is.

That difference is apparent almost immediately on the drive out of Chester – via Chester Zoo, which has me excitedly peering out of the top deck in search of giraffes and elephants (I didn't see any). After the zoo, we pass through acres of bland business park, then a vast retail city called Cheshire Oaks which looks to have been plucked from the side of a dusty mid-American interstate.

Acres of grey uniform housing estates soon follow. These might have been bright and optimistic places once, and a testament to the slum clearances of ambitious local councils after the Second World War. So much bomb damage, so many homes to build, so little time. No wonder they look a bit like army barracks. Time hasn't been kind to these estates and many now look careworn and forbidding. And all the time, the smoke stacks and massive storage tanks of Ellesmere Port and beyond are visible over the rooftops to remind people just why they live here.

I’m on the road to Birkenhead for two reasons. Firstly, it means I can enter Liverpool via the Mersey Ferry, almost certainly to the strains of Gerry and the Pacemaker’s ‘Ferry Cross the Mersey’ (Fair-r-r-rr-eee…. cross the Mer-sey….), but secondly to celebrate Birkenhead’s unique place in transport history.

As I’ve already described, the introduction of seats on the roofs of horse buses, firstly back to back a la knifeboard, and then later in forward-facing rows, established the basic design of the double decker bus we know today. However, design was to take one more radical turn before the invention of the motor bus finally swept it all away.

The horse bus was a victim of its own success. It's greatest problem was not accommodating its passengers but physically moving them. This required horses, and horses were expensive. A single team of two horses had to be fed, groomed, housed and cared for at considerable expense yet could only work for a few hours each day due to the sheer effort involved in moving a fully-loaded bus. Horse teams had to be changed four or five times a day which meant that each bus needed 10 or more horses a day just to pull it.

Eventually someone realised that replacing heavy wooden wheels on bumpy roads with iron wheels on smooth iron rails would reduce rolling resistance and allow a team of horses to pull bigger vehicles with more passengers for longer. Operators would need fewer horses, and more passengers would mean cheaper fares leading to even more passengers. It was a win-win situation.

Birkenhead has the distinction of being the birthplace of the British street tram after the very first street tramway system opened in August 1860. Built to carry passengers between the Mersey Ferry terminal at Woodside and nearby Birkenhead Park, it was the brainchild of George Francis Train, an extraordinary and flamboyant American who was also responsible for introducing trams to London.

|

| Launch day for Britain's first street tram |

However, although popular with passengers, Train's tramways had a fundamental design flaw – the rails were mounted on top of the road, not flush with its surface. As a result, everybody kept tripping over the damned things. In 1861, George was arrested and tried for the peculiar crime of "breaking and injuring" a London street. As if that wasn't bad enough, the space between the rails often filled with water which created a shallow aqueduct down the middle of road which pedestrians either had to leap across or wade through.

Having introduced Birkenhead and elsewhere to the tram, albeit to mixed reviews, Train returned to America and became involved in the creation of the Union Pacific Railroad after which he referred to himself as "Citizen Train". A restless globe-trotter, his 1870 circumnavigation of the globe reputedly became the inspiration for Jule Verne’s ‘Around the World in 80 Days’. In later years he gained a reputation for eccentricity. He adopted vegetarianism, and instead of shaking hands with other people he shook hands with himself. His final days were spent on park benches in New York handing out dimes and refusing to speak to anyone but children and animals.

His tramway idea, though, went from strength to strength once people had grasped the idea of setting the rails within the road surface. In fact, within 10 years of Train running his very first Birkenhead tram, applications to build similar systems were arriving through the government's letter box from every corner of the country on an almost daily basis. In the end, ministers were forced to introduce legislation – the Tramways Act of 1870 - to help reduce the time needed to process the huge volume of applications.

|

| Steam-hauled tram |

The first trams relied on horse power, but soon the same problems which plagued the horse bus operators - namely, the costs of maintaining dozens and dozens of horses – became a burden. Alternatives were sought, with steam engines finding popularity in the North where coal was readily available. A couple of lines were built in London using cable power but these were soon abandoned. Electricity was first adopted in Blackpool in 1885 with trams taking their power from a conduit down the middle of the road. This proved problematic, though, because the conduit regularly became blocked with sand blown off Blackpool's beaches. So when a tramway powered by electricity from an overhead cable was demonstrated in Edinburgh in 1890, it created a lot of interest. Leeds adopted this system for their own new tramway, and Blackpool and others soon followed suit.

By the start of the First Word War, Britain had more than 300 different tramway systems. Passengers numbers peaked in 1928 at 4,000 million, but their popularity waned as the new breed of motor bus began to prove itself to be quicker, more comfortable and more adaptable. By the early 1950's, with infrastructure such as rails and overhead power lines worn out and neither money nor inclination to replace them, tram operators began calling it a day. London abandoned its trams in 1952 by which time many cities had already done so. Blackpool aside, the very last tram to carry passengers in the British Isles made its final journey in Glasgow in September 1962.

|

| The tram stop at Woodside |

Today, though, a handful of restored trams have made a comeback in Birkenhead where they operate a service between the Mersey Ferry terminal at Woodside – from where Train's original tram operated – to the nearby Wirral Transport Museum. I'm keen to add a ride on a vintage tram to my growing list of vehicle types I have travelled on (I'm up to twelve already, but who's counting) so I hurry to Woodside where I find a splendidly decorative Wallasey Corporation tram with open verandas at each end of the top deck awaiting me.

I clamber aboard and we are soon swaying and clanging our way in true Edwardian style across busy roads and along abandoned docksides to the museum. The museum itself is fairly small and very much a workshop environment with part of the floorspace fenced off and littered with tools and oil cans, heavy jacks and pieces of partly-renovated trams and buses. The rest is devoted to its collection of trams, buses and motorcycles and its recreation of a motor garage from the 1930's. It's fun and informal, and I love it.

|

| Wirral Transport Museum |

I catch the tram back to Woodside and, as its half-term, I then wait amongst hundreds of harassed parents with their thousands of tired and excitable children for the Mersey Ferry and my 'Grand Entry into Liverpool', though grand in the loosest sense given my now slightly crumpled appearance after more than a week on the road.

Crossing the Mersey has to count as one of the most spectacular river crossings in the UK, largely because the Mersey is just so darned big and takes a full ten minutes to cross. Ferry boats have been making this crossing since at least the 12thcentury when monks from the nearby Birkenhead Priory would row across to the small fishing village of Liverpool on market days and could be prevailed upon to take travellers with them. It must have been quite a journey – about 90 minutes of hard, steady rowing on a fine day and a good bit longer in rough weather.

That's providing it wasn’t too rough to cross, of course. There are plenty of tales of travellers being stranded for days before being able to make the crossing, which might explain why the Priory sought and received permission from Edward II to offer board and lodgings to travellers. A few years later, his son Edward III confirmed the royal charter to operate the ferry service which meant the ferry was officially a Royal Highway. This is still marked to this day by the crowns which stand on the end of the gangway posts at Woodside and Pier Head.

Rowing eventually gave way to sail and then the age of steam arrived, bringing with it what must have been one of the most terrifying steam ferries imaginable. This was an odd looking thing with twin hulls and a huge paddle wheel down the middle which, by all accounts, was very unstable and difficult to handle. Even more worrying was it's name. Now remember, steam was very much a new technology at this time, unproven and sometimes prone to explosion. Now consider, if you will, the logic of naming that very first steam ferry after an Italian mountain with a reputation for exploding with considerable and unexpected violence. Yep, that's right, they decided to call it 'Etna'. It's amazing they ever persuaded anyone to crew her, let alone buy tickets to board her.

Her Majesty: “I name this ship the SS Exploding People Killer. God bless her.. and God help all who sail in her.... (muted cheers)

|

| Mersey Ferry |

Whatever message the Etna’s name may have sent to its passengers, and to those of its sister ship the Vesuvius (no, really, I’m not making this up), what it did guarantee was that for the very first time the Mersey ferries didn't have to wait for the wind and tide but could operate to a regular timetable. For the first time, travel over the Mersey became predictable and commonplace, if a little scary.

The opening of the world's first purpose-built underwater railway beneath the Mersey in 1886 was predicted to spell the end of the Mersey Ferry but in fact it continued to thrive. It was only with the opening of the Mersey road tunnel in 1934 that custom began gradually to fall away and by the 1970's the ferry was on its knees, so to speak. It might have disappeared for good but someone came up with the idea of re-modelling it and re-launching it in 1990 as a heritage and visitor attraction and today it thrives.

I shuffle my way on board for the short crossing to Liverpool's Pier Head, stepping carefully over prostrate tantruming children and around snarling parents onto a ferry which closely resembles a war zone. This is strangely appropriate given the Mersey ferries' tradition of wartime service. Take the Iris and the Daffodil, for example, who were requisitioned by the Admiralty in 1918 to take part in a daring raid on Zeebrugge. The Navy chose them because of their shallow draught which they thought would make them ideal for landing a party of Marines at the entrance to Zeebrugge harbour.

|

| Iris and Daffodil ready for battle |

So, flanked by HMS Vindictive, the Iris and the Daffodil went into battle where they got badly beaten up but somehow made it back. After a quick refit to repair the shell holes, they went straight back into service on the Mersey and to recognise their part in the raid, King George V granted Wallasey Corporation, whose ferries they were, the right to add the 'Royal' prefix to their names. They bear that monikor to this day.

A Mersey Ferry captain's job is trickier than it looks. Weighing in a 500 tonnes and subject to some of the strongest tidal flows in Britain, people who know about such things describe manoeuvring the Mersey Ferry as a bit like driving a bus on ice. Our captain seems to have its measure, though, and we are soon pulling alongside the landing stage at Pier Head under the watchful gaze of the Liver Birds standing on top of the Liver Building. The helpful and entertaining on-board commentary suddenly breaks into Gerry and the Pacemaker's eponymous 'Ferry Cross the Mersey' as we dock and I am swept along in the headlong rush to get away.

Entering the City of Liverpool by ferry has to be one of the finest ways of entering any city in Europe. The view from the river of the stately Liver Building, the broad-shouldered Albert Docks and the twin cathedrals on the slopes beyond ranks as one of the finest cityscapes in the world. Manhatten? Pah. Give me Liverpool anytime - it's a view I never tire of.

I'm staying within the Albert Dock tonight and taking my ease under barrel-vaulted ceilings of warm brick supported on cast iron pillars – not unlike Shrewsbury's Ditherington flax mill, as it happens – with the fast flowing Mersey on one side and the still dock on the other. It's all rather fabulous and the view across the dock at the Cunard and Liver Buildings at sunset is truly sensational.

Mind you, at these prices it ought to be…

NEXT: Liverpool – Manchester - during which I ponder on the history of bus tickets, reflect on past experiments in alternative ways of powering a bus, and visit an enormous transport museum even though technically it was closed for the day.

Map courtesy of those awfully nice people at Google

Pedantic point: When you say the British Isles in relation to the last trams running, you would be more correct to say Great Britain or the United Kingdom. Because the term British Isles includes the Isle of Man, where electric (and horse) trams also never stopped running!

ReplyDelete