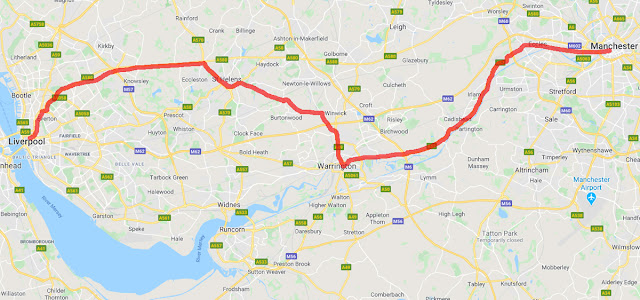

Day 16 - Beating A Path Along The Mersey (roughly)

Liverpool to Manchester

There's something about Liverpool that I never tire of. It's got character, vivacity, a proper local accent. You can forgive it being a bit cocky at times because, frankly, it has an awful lot to be proud of.

After all, the city does hold the Guinness Book of Records' title of the UK Capital of Pop. More musicians with their origins in Liverpool have had a number one hit than from any other place in Britain, but it doesn't start and end with the Mersey Beat. The city also has the largest collection of Grade II-listed buildings outside London – 2,500 of them, plus 250 public monuments. The Walker Art Gallery houses one of the best collections of European art outside London. The city is also home to the Tate, and the largest cathedral in Britain.

And then there's Superlambanana. How could you not love a place that commissions something as daft as this? This bright yellow sculpture, part lamb, part banana, was created by the Japanese artist Taro Chiezo to celebrate the opening of the Tate Gallery in Albert Dock. It stands nearby as both a celebration of Liverpool's history - sheep and bananas were common cargos on the city's docks, apparently – and possibly a comment on the dangers of genetic engineering. A further 125 appeared in 2008 during its European Capital of Culture year. Quite brilliant, and quite, quite mad.

Liverpool also played a role in the American Civil War and was the only city in the world to have a Confederate Embassy. The very last act of the whole American Civil War actually took place out on the Mersey when the last confederate raider surrendered to the Lord Mayor of Liverpool.

With all this historical stuff to ponder I'm inclined to linger, so I allow myself a brief wander along the riverside in the morning sun before making for the bus station. Logic dictates that from Liverpool I should now be heading north towards the Lake District and the Scottish border. I am, after all, en route to John O’Groats.

Instead, I’m heading east, roughly – very roughly – along the course of the River Mersey.

|

| Queens Square bus station |

I haven’t quite taken leave of my senses, though you might have expected me to after two long weeks on the road. In fact I’m far from being tired of bus travel. It’s just all so… interesting. I mean, every bus journey is subtly different from the last and I find that endlessly interesting. And what’s really drawing me eastwards is an appointment in the Peak District and two more transport museums.

I arrive at Liverpool's Queen's Square bus station just as my bus pulls in so I jog briefly to its door. I tell my driver where I'm heading and he recommends a day ticket. Actually, I'm finding drivers generally pretty helpful in this respect, often making complex arithmetic calculations in their head to ensure they give me the cheapest ticket. Nice people.

I grasp my flimsy paper ticket and find a seat. I call it a ticket - it looks more like a till receipt. You might be surprised to hear that even bus tickets have their devotees who collect them in the way that others collect first editions. Look on the internet and you'll find hundreds of individual tickets, mixed lots, rolls of blanks and all manner of ticket paraphernalia for sale at any one time. I suppose part of the attraction might be that tickets were never meant to be kept so although hundreds of billions must have been issued over the years relatively few survive. Those that do are therefore collectable, apparently.

We take them for granted now, but tickets were far from universal at the start of the bus age. It wasn't until 1881, when the London Road Car Company introduced them, that bus passengers first received a ticket for their journey. Until then it was left to the conductor to collect the fares and, at the end of his shift, hand in what he thought the bus owner would expect to see, leaving the crew to pocket whatever was left.

Not surprisingly, bus crews didn't take kindly to the new regime of one ticket per journey, especially as inspectors were also appointed to check that conductors were doing what they were meant to. In 1891 Thomas Sutherst, who had founded a trades union for tramway and omnibus workers, led his men out on strike ostensibly to demand a shorter working day, something which seems quite reasonable given that crews generally worked a 15 or 16 hour day, seven days a week. But nobody was in any doubt about the real cause for complaint. In the end, the strike was resolved by the companies agreeing to a shorter 12 hour day and increasing wages a little.

The flimsy Day Saver my driver has handed me will take me all the way to Warrington at the cost of £4.20 – and back again if I want, or on any other Arriva service in the area that day. I later work out that the fuel cost alone for the drive to Warrington via St Helens in a car delivering a frugal 35 miles to the gallon would be £4.19. And that's without the cost of servicing, depreciation, insurance, road tax, parking or any of the hundred or so other expenses associated with car ownership. That's truly amazing value. Remind me to tot this all up at the end, will you?

We grind slowly out of Liverpool through a dense web of brick terraced streets. The city centre seems entirely ringed by these narrow densely-packed terraces; this is a quite different Liverpool to the one viewed from the Mersey Ferry - no shining glass apartments, no broad paved streets, no bright splashing fountains, and no carefully-nurtured trees casting their dappled shade on well-groomed passers-by. Poorer, grittier, you wonder whether anything of the riverside’s brave new world has benefited the people who live out here, just a mile or two out from the city's increasingly cosmopolitan city centre.

We are soon running into Knowsley which has a pleasing and unexpected 'village' feel. We pass the Knowsley Museum with its proud sign, a rather nice church, a stately Victorian registry officer, and Knowsley's Family Martial Arts Centre. Family martial arts? Perhaps they believe that a family that affrays together stays together. Can’t help feeling that might cause parental control problems, though. How can any parent be expected to discipline their kids if, at any minute, little 10 year-old Wayne could have you on the floor with a Uki Otoshi (that's a judo throw, by the way).

I spot another sign on the road out of Knowsley across the front of a pub which proudly, and in letters at least half a metre high, boasts that their kitchen has received a hygiene rating of four stars out of five. They're obviously rather proud of this, but then ‘four out of five’ does beg the question - what exactly was it that the Environmental Health Officers saw on their inspection which led them to say, "Well, it's generally quite good but...,

'But' what? But for that huge weeping fungus growing out of the ceiling? But for the seething nest of ants under the fridge? Does four out of five mean 'nearly no cockroaches'?

In football parlance - and with two Premiership teams it's practically a second language around here - I'd say that comes close to an own goal.

|

| North West Transport Museum |

My next stop is St Helens and the North West Transport Museum, my fourth transport museum of the trip. Conveniently this is just around the corner from the bus station which is none too surprising given it is housed in a former bus depot which used to be a tram depot before that, and a horse tram depot before that. Plenty of context, then.

I was arriving on a Friday so I knew it was closed, but I was hoping I'd be able to find someone inside who I might persuade to come to the door and let me have a quick look around. Sure enough, one of the museum's volunteers was relaxing at a table amidst the museum exhibits and he spotted me with my nose pressed glumly against the window and agreed to let me in for a peek.

This is a huge and impressive place. The museum is blessed with a glass roof which absolutely floods the main exhibition area with light, illuminating a vast airy interior housing dozens of buses and numerous other vehicles. There's also a lecture theatre and a huge workshop area which the public don't normally see but which gives you a glimpse of the work that goes into the conservation of large commercial vehicles like buses.

I wander around admiring the stately and sometimes dilapidated vehicles, then come back and settle down for a chat with George, one of the volunteers who is filling in time whilst waiting for his car to be serviced. He explains that pretty much everything on show is privately owned by ordinary people like him.

I wander around admiring the stately and sometimes dilapidated vehicles, then come back and settle down for a chat with George, one of the volunteers who is filling in time whilst waiting for his car to be serviced. He explains that pretty much everything on show is privately owned by ordinary people like him.

“We charge people £60 a month to keep their vehicles here, but anywhere else would be £80 or £100. The income is useful to us and it means we have plenty of exhibits and they help pay for the museum's costs.”

“It's not an expensive hobby. For example, I have an AEC Regent double decker over there and I've just insured it fully comprehensive and it only cost £120. Which is not bad, really.”

Visions of myself at the wheel of an old bus, my very own bus, swim into view so I ask him if restoring an old bus is something that anyone could do. Encouragingly, he thinks it is especially if you are part of a museum like this and people can share their skills.

“The trouble with buying an old bus is you never know what you have under the panels until you take them off to see what the frame is like. That’s where the rot can be and that's where your problems can start. Especially with really old buses with wooden frames. It can be a right job making all those complicated curves and that, and it can cost a fortune. It can take ages to do it right.”

Not so easy, then...

One of the museum's more unusual centrepieces is a rather knocked-about double decker which has been rather crudely converted into a mobile home. It looks pretty shambolic but it has a fascinating history.

By the late 1940’s after six long years of war, Britain's economy was in a mess. The country was effectively bankrupt and the call went out to industry to “Export or Die'. Manufacturers, and especially vehicle manufacturers who had large production capacity and new skills after years of building vehicles for the war effort, were called upon to answer the call. Soon all shapes and sizes or cars, vans, lorries and buses were being promoted and exported overseas, helping to bring in much needed currency.

|

| Museum workshop |

This particular vehicle, an AEC Regent, was exported to Australia after the war as a chassis and then built as a bus by a local Aussie coachbuilder. It entered service on the streets of Sydney in 1948 and was still in service more than 20 years later with more than 600,000 miles already under its wheels, but it wasn't finished yet.

In 1970 it was involved in a tail-end accident and withdrawn from service. The company felt the damage was too severe for repairs to be cost-effective so it was sold to the Tunin family of New South Wales who had it repaired and converted into a mobile home complete with a shower, kitchen, fridge, washing machine and bunks upstairs. The family toured Australia for several years, crossing deserts and venturing right into the Outback before deciding they'd quite like to see Europe now. So they topped up the fuel tanks and set off.

The year 1978 found them in Britain and having toured the whole of the British Isles they arranged to leave their bus at the North West Transport Museum former premises at a nearby disused RAF base while they returned home. In 1985 they were back and off on their travels again, this time to Morocco, the Alps, Russia and all points between. When they returned, they decided that the cost of repatriating their beloved bus was just too high so they donated it to the museum. It stands today practically as they left it, still wearing its shabby Sydney Transport paintwork and with its kitchen sink and washing machine intact, just waiting to hit the road again. Apparently, the engine still runs.

I was wondering why such a fascinating and well-laid out museum is only open at week-ends. George explains that they do open for school visits during the week, but that generally staffing the museum could be difficult.

“We are always looking for volunteers with particular skills who can be of use around the place, but its not always easy to find them. We have a lot of people involved in the museum and paying to keep their vehicles here, but there's lots we don't see very often. That's why we only open at week-ends and bank holidays – we just can't get the people to staff the museum.”

|

| Technobus |

I thank my host for letting me have a look around and make my way back to St Helens bus station, thinking that if I lived here then I would definitely become a volunteer. Might even have a bus of my own...

As I'm about to leave St Helens, I spot a curious little bus parked up by the bus station. It is a third of the size of a normal bus and has six wheels, and a door – and driver – on the wrong side. I take a closer look and discover that it is an Italian Technobus electric bus, one of a number that Merseytravel had been evaluating but which seven years later seemed to be still operating on the streets of St Helens. Odd to look at, it is certainly nippy enough and seems to be cutting through the traffic with ease. I regret not having time to take a ride on one to add another form of public transport to my growing list. Not that I'm keeping count, mind. That would merely confirm my children's belief that I am, after all, a complete anorak. It's thirteen, by the way...

Alternative fuel sources has been a hot topic in the bus industry for some time. We've had experiments galore – battery-operated buses like this one, buses fitted with gas turbines generating electricity to power the wheels, hybrid buses, fuel cell buses – yet you'd be wrong to think that this was in any way new. In fact, some of the very earliest motor buses even today sound positively cutting edge.

Take South Shields' very first municipally-owned bus. Affectionately named 'The Red Sardine' – and rather less affectionately 'The Harton Boneshaker' – this was one of four vehicles purchased in 1914 by the council and powered not by petrol but by electricity via Edison accumulators. Quiet and fume-free, these battery-powered buses could only manage 45 miles between charges but they proved useful during the inevitable petrol shortages of the First World War. Unfortunately, replacement batteries couldn't be found after the war so they were converted to run on petrol.

|

| Tilling-Stevens petrol-electric bus |

Petrol-electric buses, using a conventional petrol engine to generate electricity to drive electric motors attached to the rear wheels, were more common in the USA than in the UK but they had their British fans. They were considered easier to drive than a bus with a gearbox, and smoother and much quieter than their petrol counterparts, many of whom relied on noisy chains to deliver the drive to the rear wheels.

When the London bus operator Thomas Tilling decided to replace their 220 ageing horse buses with motor buses, he reckoned it would be easier to train his equestrian drivers to drive a bus if they didn't have to teach them to use a gearbox. So in 1906 he set up the firm of Tilling-Stevens Ltd specifically to manufacture buses with petrol-electric transmission and no gearboxes, with his first model appearing some five years later. The company continued to build petrol-electrics until 1926 by which time they could no longer compete with the new generation of motor buses.

Of course, none of this would have been possible without Nikolaus Otto, considered by many to be the inventor of the four-stroke internal combustion engine, even though it was Gottlieb Daimler, a young engineer employed to manage Otto’s company, who perfected his design and produced the first efficient petrol engine, and the first motor vehicle. Unfortunately, the two fell out and this lead to Daimler taking his improved engine design and setting up his own company with his business partner Wilhelm Maybach.

Interestingly, in March 1886 Daimler and Maybach installed one of their engines in a wooden stage coach which they then proceeded to drive along a road in Stuttgart achieving speeds of 10 miles per hour, the first motor vehicle ever to do so. Technically, this vehicle could constitute the first ever motor bus though it is not known whether it ever carried any passengers.

Daimler's engines eventually came to the attention to a young British engineer called Frederick Simms who secured the rights to all of Daimler's patents for Britain. By 1896 he had set up The Daimler Motor Company in a disused cotton mill in Coventry with the intention of building cars. It was a highly auspicious year to do so, as the government had just enacted the Locomotive and Highways Act, increasing the speed limit for motor vehicles from 4 miles per hour to 12 and doing away with the need for a man to walk in front with a red flag.

|

| Milnes-Daimler |

Then in 1902, the long-established tramcar builders GF Milnes and Daimler came together and within 12 months had launched the Milnes-Daimler 16hp single deck motor bus to considerable acclaim. Eastbourne Council bought four of them almost immediately, becoming the first municipality in Britain to operate motor buses. Milnes-Daimlers were also used by the Great Western Railway to provide the bus service between Helston and The Lizard I mentioned on Day 1 of my trip. Their vehicles would set the shape of buses for years to come.

It's getting late so I board my own bus for the onward journey east. We are soon out of St Helens passing row after row of terraced houses, most trying hard not to look like their neighbour– some stone-clad, others rendered, still more painted, all of them trying to look smarter and a little less humble than they are. A nearby semi-reclaimed colliery spoil heap suggests a long gone mining industry and explains the presence of so many cheap, brick-built terraces of workers homes.

It's a strange mix, this area. It's densely populated but then there's the occasional farm, too. Refinery chimneys poke over the rooftops one minute, then just down the road there is a sign advertising fresh new Cheshire Cheeses for sale. Cereal crops, motorways, grubbed out hedges, brightly-flowered parks, spoil heaps – it's all here, but its a real untidy mix.

We swing into Warrington town centre with its jumble of roads and concrete, though when you look a little closer and ignore its bulky shopping mall then there's clearly a nice little town somewhere under all those bland shop fronts. The streets seem designed more for the motorist than the shopper though, so I retreat back to the huge, glass-walled bus station, a truly splendid affair which would rival any airport terminal. It's so palatial that I unconsciously wipe my feet as I enter.

|

| Warrington's bus station |

I quickly find an onward bus to Manchester. We seem to have a deeply melancholy driver who guides us on our unexceptional journey through an unexceptional urban landscape along roads which appear to be little more than crudely-filled ruts. The bus is practically shaken to a standstill in Irlam, where a rather crotchety lady gets on.

“Do you know if there's a 67 due?” she demands.

“I haven't seen one,” admits the driver. “But they run every 10 minutes so...”

“There's been none for 20 minutes!” she spits, as she grumpily gets on followed by a gentleman for whom life appears to have lost all meaning. Within seconds of the bus starting, though, she's pressing the bell and making her way back to the front. We must have travelled all of 200 metres.

“You know,” she complains to her grey, weary husband, “I bet one goes sailing past before we get to the bus stop...”

She gets down off the bus followed bleakly by her husband, who throws a meaningful glance at our unhappy driver. Both seem to understand what the other is going through, but the knowledge doesn't seem to make either of them any happier.

We duck under the M56 and cross the Manchester Ship canal a couple of times before the elaborate domes of the Trafford Centre loom into view. From its cutesy little bus station, it looks as artificial and insubstantial as a film set. I stay on the bus.

|

| Metrolink tram, Eccles |

We soon pull into Eccles Interchange where I transfer from bus to Metrolink, Manchester's splendid tram system. I'm slightly disappointed not to find dozens of itinerant Eccles cake sellers loitering around, nor anywhere I can easily buy one. I think about popping into a nearby supermarket but of course there's no certainty that supermarket Eccles cakes are made anywhere near Eccles. After all, I've already passed what looked like the biggest Carlsberg brewery in the world brewing the finest Danish lager – and that was in Northampton, for goodness sake. And what about Shrewsbury biscuits...

I high-tail it over to the nearby tram platform to complete my journey into Manchester. I have a growing fondness for trams like these. They seem impossibly dangerous things to have anywhere near a road so a journey by tram is constantly entertaining. Will we crash into that refuse truck? Will that taxi get out of the way in time? Will that guy in the suit suddenly realise there's a tram breathing down his neck? Ooh, lovely!

I arrive at my hotel ready for dinner, so after a quick shower I’m back on the streets en route to Piccadilly Gardens, by day a vast green square filled with people chatting and eating their packed lunches, but at all times a major transport interchange where dozens of bus services intertwine with the Tramlink. I'm looking for a bus to the Curry Mile among the melee. Fortunately there is a transport information centre close by and I soon find the right service. My driver seems a practised curry user, too, and helpfully points out a number of restaurants I might wish to try before dropping me off and wishing me bon appétit.

It's a great end to a pretty good day. OK, so the scenery hasn't been brilliant but my channa curry certainly is, and travelling everywhere by bus means that I can have yet another beer to wash it down with. Oh, I am so enjoying this...

Waiter!

NEXT: Manchester to Glossop – where I visit yet another transport museum, find myself taking a ride on a much-maligned bendy bus, and then observe some pretty disappointing behaviour by the driver of my bus to Hyde.

Map courtesy of those awfully nice people at Google

Comments

Post a Comment